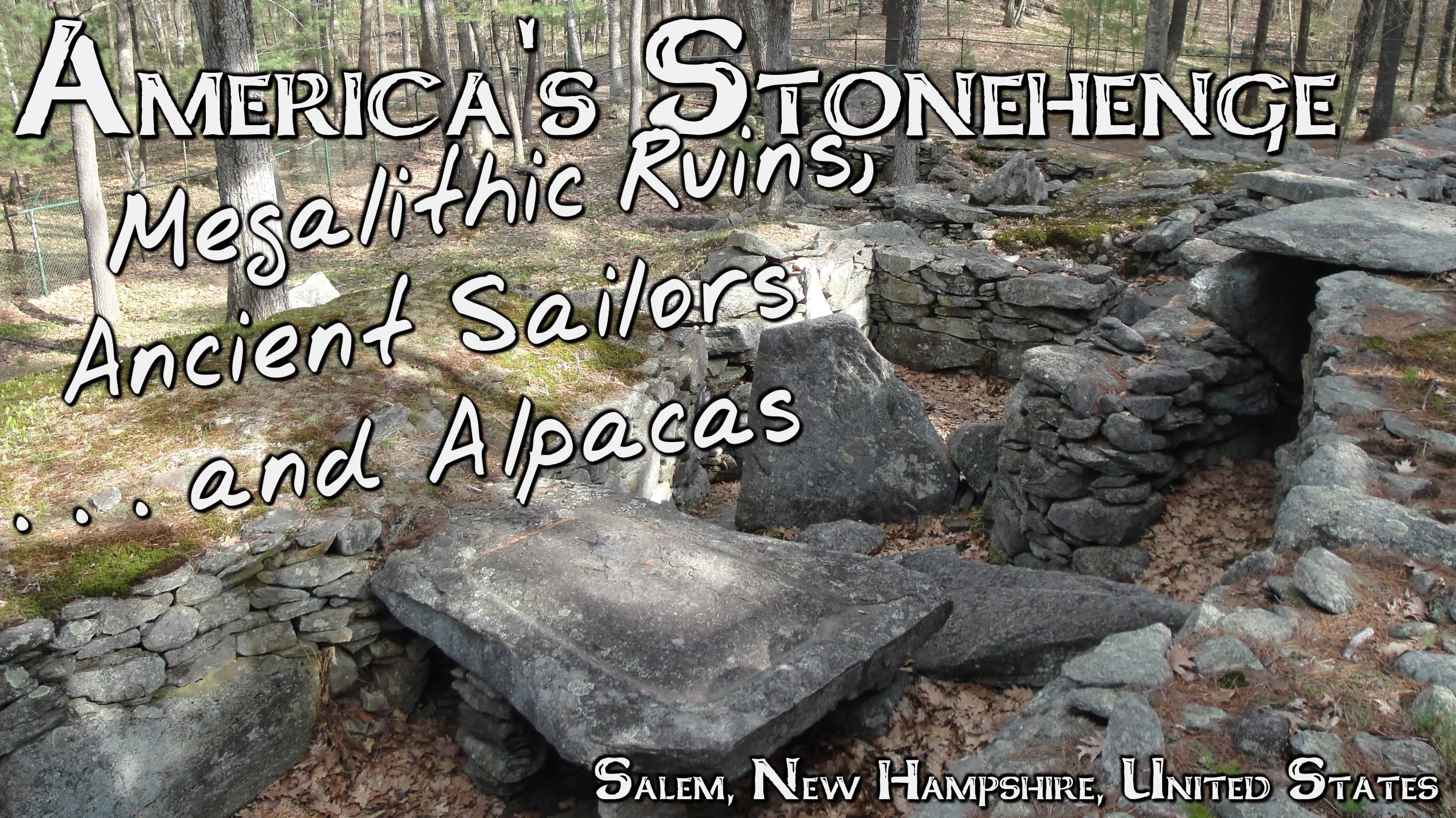

North of Boston, less than an hour away, lays an interesting archaeological site. The greatest debate about it is whether or not it is authentic. If it is, it could rewrite many of the accepted notions of pre-Columbian American culture, or pre-Columbian European contact. And if it isn’t authentic, it means someone spent a lot of time doing some unnecessary landscaping in some unknown effort. After looking at it for myself, I couldn’t decide one way or another.

The day started with me asking the desk clerk at the HI Boston where the best place to rent a car was. They recommended someplace near the city center. I searched for a car rental on Google Maps on my iPhone and found one in the Prudential Center.

It took me a little while to find the rental agency, as they were below the basement floor of the center, adjacent to the parking garages. Once I did, I had the choice of a Chevrolet or a Volkswagen. I chose the VW just because I was so used to Chevys.

It was odd getting back on the road again. The last time I drove in a city like this was in Chicago, passing through all the ridiculous interchanges to simply go south of the city toward St. Louis and New Orleans, rather than into the city itself.

The drive toward New Salem was uneventful, complete with the unmemorable passing of the “Welcome to New Hampshire” sign. When I got off the interstate, I followed a couple lesser highways with vague signs pointing toward “America’s Stonehenge.”

When you pull in to the site, it’s not exactly overwhelming. Granted, I did get there in the last hour it was open. Anyone with any experience in legitimate archaeological sites can immediately spot a few things off about this place. Of course, it is privately run, not a state or national park.

The first thing is the alpaca. Why does the “first megalithic site in the US” have a caged herd of alpacas at it? I can understand it may add another draw to the site. But, it certainly does nothing to help its case for academic legitimacy.

After that, there was the map. Inside the visitor center/gift shop, there is a map of supposed transatlantic crossings that could have occurred. I have done a good deal of my own research into this subfield of speculative archaeology, and this map has its many facts way off.

After leaving the gift shop, you are led past the alpaca cages up a guided, stone-enclosed path up to the site. This is one of the places, beyond the unresearched map and alpaca, that it becomes hard to tell the legitimacy of this site.

As stated before, the path is lined with placed stones. So is the site itself. And, at first glance, there is no change their form, their color, or their makeup. Perhaps in the scale, but not much else.

Still once you get into the main, what I will very reluctantly call “citadel” of the site, the view is different. If it were an ancient site, it quite obviously is never one that was inhabited. The stone chambers and passages would never have comfortably fit a few individuals, much less any sort of population. It also lacks the symmetry of any European ceremonial sites that I have ever studied or read about.

However, while this holds true for the citadel (central structures), there is a symmetry established in the greater site. There are index stones spaced on the perimeter of the site with are an astronomical calendar aligned to solar events throughout the year. They are also seemingly placed near intentional clearings in the forest so that the solar event may be seen along the distant horizon. Again, whether this clearing is the act of the suggested ancient inhabitants or of the modern settlers remains unresolved.

The popular story of the site goes that it was discovered by John Pattee, who lived nearby, in the early 1800’s. Some texts say that there were “intact caves” that he used for storage. This opinion holds that Pattee simply constructed this along with his family or other locals for reasons now unknown.

In the early 20th Century, William Goodwin acquired the property, giving it the name Mystery Hill. He was convinced of its European origins and went to work reconstructing how he thought it originally looked, doing more damage than help to the site and anyone who would want to examine it scientifically in the future.

Some of these buildings (again, the term used loosely) are intriguing and certainly required some sort of architectural skill to construct. And a few of the stones are large, as in too large for the lifting capacity of only a handful of people. What’s more, these are not simply placed at the base, but lifted as top or intermediate stones, meaning there was some level of construction before these large stones were added.

That being said, while a few of the stones are certainly large enough to be megalithic, the site as a whole is not, and is mostly made up of stacked stones small enough to be lifted into place by a single person.

The conundrum becomes not whether or not the 19th or 20th Century owners would be able to make this, because in all actuality they would without an enormous amount of difficulty. It is why would they go through the trouble of constructing something like this?

I spent around 45 minutes examining anything in the site that I could before they closed. I went there with higher expectations than were met by the Mystery Hill site, largely based on the amount of diffusionist literature I had already been exposed to about the site. It’s not that I wouldn’t have liked reading about the topic on the other end of the academic spectrum; however, the topic is rarely addressed in traditional archaeology.

I left America’s Stonehenge unconvinced either way on its authenticity. The size of many of the stones and the manner of construction certainly make this something more than a farmer’s backyard project, but it’s very far from the smoking gun needed to prove pre-Columbian Transatlantic travel that some diffusionists make it out to be, when the fact remains that none of them can even attribute a common culture they think might have constructed it.

I certainly don’t think it’s out of the question that this was originally a Native American ceremonial site, a possibility that is often overlooked in regards to the site, preferring the romance of the pre-Columbian Europeans. The only trouble with this idea is that stone construction was not commonplace, if existent at all, in North America outside of the U.S. Southwest and Mesoamerica.

However there is a good deal of exposed rock in the area, including at the site itself. It’s not inconceivable that with easy access came the idea to use it to construct a ceremonial site. In excavating an in situ (untouched and in its original place) megalith, numerous lithics and flakes indicating toolmaking in a manner consistent with Native American methods.

Driving south out of the site, I took notice of something I hadn’t on the drive there. A large number of the properties along the nearby roads were lined with stacked stones in their landscaping. Many were almost identical replicas of those that lined the path of Mystery Hill, not exactly helping the current owner’s case that it is an entirely original ancient site.